- Read offline

- Access all content

- Use the in-app Map to find sites, and add custom locations (your hotel...)

- Build a list of your own favourites

- Search the contents with full-text search functionality

- ... and more!

Chíos

Homer, mastic, rockets and mosaics

Soak me with jars of Chian wine and say ‘Enjoy yourself, Hedylus. I hate living emptily, not drunk with wine.’ Hedylus, c. 280 BC

Chíos is a uniquely fascinating and wealthy island, the fifth largest in Greece, celebrated for its shipowners, friendly good humour, its delicious tangerines and the gum mastic that grows here and nowhere else in the world in 34 fascinating ‘mastic villages’—not surprisingly its nickname in Greek is myrovólos (Μυροβόλος Χίος, the aromatic).

Chíos has lush fertile plains, thick pine forests (sadly many were burned in the wildfires of 2025) quiet beaches, Mediterranean scrublands tufted with maquis and startlingly barren mountains that bring to mind the ‘craggy Chíos’ of Homer, who may have been born on the island. Its architecture is unique and varied, and its church of Néa Moní has some of the finest 11th-century Byzantine mosaics anywhere, now granted World Heritage Status by UNESCO.

Unlike other islands, Chíos has been slow to embrace tourism, plus the lack of international flights has put it off the radar for many international tourists. But in recent years some locals have done their bit to promote the island. For instance, old paths have been restored, and new ones laid out: see Chios Hiking for maps and descriptions to over 20.

History

Inhabited in the Late Neolithic (c 4500 BC), Chíos was colonized by pre-Hellenic seafaring Pelasgians who left walls near Exo Dídyma and Kouroúnia and a Temple of Zeus on top of Mount Pelinaío. The Mycenaeans followed, and were in turn usurped in the 9th or 8th century BC by Ionians from Evia (it was their northernmost settlement); one tradition asserts that Homer was born here shortly after.

By then Chíos was a thriving, independent kingdom, founding trade counters (emporia), notably one called Voroniki in Egypt. It was famed for its mastic and wine (especially from the medicinal arioúsios grapes), and for its sculpture workshop and system of government, studied by Solon and adapted for use in his Athenian reforms. Around 490 BC, a Chiot sculptor Glaucus invented the art of soldering metals; on the minus side, Chíos was the first state in Greece to engage in slave-trading.

One of the twelve cities of Archaic Ionic Confederacy, Chíos joined its fellow Ionian cities in the Battle of Lade (494 BC) in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Persian yoke (a rebellion that began on Naxos), but after the Battle of Plateía and the final defeat of the Persians, it regained its independence, and held on to it even after Athens made its other allies into tribute-paying dependencies, until 412 BC when it revolted, only to be crushed.

Chíos allied itself with Rome and fought the enemy of the Empire, Mithridates of Pontus (83 BC), only to be defeated and occupied by Mithridates, although it was liberated after two years when Mithridates was defeated by Sulla.

In the 4th century AD, Chíos made the mistake of siding against Constantine the Great, who conquered the island and carried off many of the island’s famous sculptures to embellish his new city of Constantinople—including the four splendid bronze horses that the Venetians in turn snatched during the Fourth Crusade to stick on the facade of St Mark’s.

Genoese and Ottoman Chíos

In 1261, the Emperor Michael Paleológos gave Chíos to the Giustiniani, the Genoese family who helped him reconquer Constantinople from Venice and her Frankish allies. In 1344, the Giustiniani chartered a company called the Maona (from the Arabic Maounach, or trading company) of 12 merchants and shipowners, who sold its precious mastic and governed the island until 1566 when Chíos was lost to the Turks.

The Sultans loved Chíos, especially its sweet mastic, and they granted it more privileges than any other Greek island, including a degree of autonomy. It became famous for its doctors and chess players; elsewhere in Greece, the cheerfulness of the Chiots was equated with foolishness. This came to an abrupt end in 1822. Although the islanders had refused to join in the revolt, a band of 2,000 ill-armed Samians disembarked on Chíos, proclaimed independence and forced them to join the struggle.

The Sultan, furious at this subversion of his favoured island, ordered his admiral Kara Ali to make an example of Chíos that the Greeks would never forget. In two weeks, the Turks slaughtered an estimated 30,000 Greeks, and sold another 45,000 into slavery; the Sultan’s sweet tooth dictated that only the mastic villages and their inhabitants survived. All who could fled to other islands, especially to Sýros (where they picked up useful lessons about owning ships), before moving to England, France and Egypt.

News of the massacre made headlines across Europe; Delacroix painted his stirring canvas (now in the Louvre) and Victor Hugo sent off reams of rhetoric, and contributed to support for the Greek war of independence. On 6 June of the same year, the Greek Admiral Kanáris took revenge on Kara Ali by blowing him and 2,000 men up with his flagship.

In 1840 Chíos attained a certain amount of autonomy under a Christian governor, but in 1881 suffered another tragedy in an earthquake that killed nearly 4,000 people. It was incorporated into Greece in November 1912.

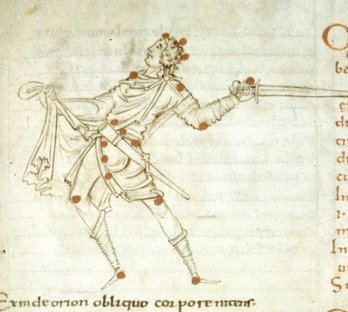

Mythology: Orion on Chíos

Chíos was favoured by Poseidon, and is said to owe its name to the heavy snowfall (chioni) that fell when the sea god was born. Vines were introduced to the island by Oenopion, son of Ariadne and Theseus. Oenopion pledged his daughter Merope to the handsome giant hunter Orion, on the condition that he rid Chíos of its ferocious beasts, a task Orion easily performed – it was his boast that given time he could rid the entire earth of its monsters.

Rather than give Orion his reward, however, Oenopion kept putting him off (for he loved his daughter himself), and finally Orion in anger raped Merope. For this the king poked out his eyes. Orion then set out blindly, but the goddess of dawn, Eos, fell in love with him and persuaded Helios the sun god to restore his sight.

Before he could avenge himself on Oenopion, however, Orion was killed when Mother Earth, angry at his boasting, sent a giant scorpion after him. Orion fled the scorpion, but his friend Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, killed him by mistake. In mourning, she immortalized him in the stars.

Chíos Town

First-time visitors to Chíos arriving by ferry often wonder what they’ve let themselves in for. The long harbour-front of Chíos Town (pop. 27,000) doesn’t even try to look like a Greek island, with its tall buildings and a brightly lit bars and tavernas; throngs saunter and dawdle, and on summer evenings every single table is full.

Badly hit by an earthquake in 1881, the town that arose from the rubble is slick and glossy, full of new apartment blocks and high-rise offices, and perhaps more fast-food joints than strictly necessary. There’s even a bowling alley!

Yet after the first surprise, the town – a sister city of Genoa, for old times’ sake – is a likeable enough place. Most of what survives from the Turkish occupation—now a rather chummy neighbourhood in the throes of restoration— is enclosed within the Byzantine fortress, which more or less follows the lines of the Macedonian castle destroyed by Mithridates. After 1599 only Turks and Jews were allowed to live inside; the Greeks had to be outside the main gate or Porta Maggiore when it closed at sundown.

Within the walls is a ruined mosque and a Turkish cemetery with the tomb of Kara Ali, ‘Black Ali’, author of the massacre of Chíos. The tomb’s surprisingly unvandalized state is perhaps a testimony to the tolerant, easygoing nature of the Chiots, remarked on since antiquity. In a closet-sized prison by the gate, Bishop Pláto Fragiádis and 75 leading Chiots were incarcerated as hostages before they were hanged by the Turks in 1822.

The small Justiniani Museum nearby in Plateía Frouríou, contains detached frescoes, carvings and early Christian mosaics. The main square, Plateía Vounakíou with its cafés and plane trees, is a few minutes’ walk away. It has a statue of Bishop Pláto Fragiádis, and in the municipal gardens behind the square is a flamboyant one of Kara Ali’s avenging angel, ‘Incendiary’ Kanáris, a native of Psará.

Plateía Vounakíou’s crumbling mosque is marked with the Tugra, the swirling ‘thumbprint of the Sultan’ that denotes royal possession. Tugras, though common in Istanbul, are rarely seen elsewhere, even in Turkey, and this one is a mark of the special favour that Chíos enjoyed. Today the mosque houses the Byzantine Museum, with a collection of art, tombstones and other old odds and ends too big to fit anywhere else.

The south end of the square is closed by the Homerium, a municipal cultural centre with frequent exhibitions; others are held in the old public baths on Syngrou, now the Chíos Public Art Gallery which also features a permanent collection of paintings by the island’s artists.

South of Plateía Vounakíou near the cathedral, the Koraes Municipal Library was founded in 1792, but destroyed during the Ottoman massacre. Its founder, Adamantios Koraes, immediately set about replacing it, with donations from across the Philhellene world. The most precious work is the famous Déscription de l’ Egypte —the fourteen illustrated volumes issued 1809-22 and donated to Korais by Napoleon.

Today it claims to be the third largest in Greece with 135,000 volumes; the same building houses the Folklore Museum (same hours), the private collection of London scholar Philip Argéntis, scion of an old Genoese-Chiot family who got tired (with good reason) of looking at his family’s portraits. Other displays feature Chiot costumes and handicrafts, bric-à-brac, and engravings of 18th-century Chíos.

The large 1970s vintage Archaeology Museum, 5 Michálon Street near the Chandris Hotel, contains typical island finds, some bearing the ancient Chíos symbol, the sphinx holding an amphora. The main permanent exhibit is ‘Chios of the sea, city of Oenopion’ with everyday items going back to Neolithic times up to the Roman era (including a colourful mosaic of a hunt) and finds from a Mycenean cemetery.

The Chíos Nautical Museum, 20 Stefanou Tsouri, is a shipping fanatic’s fantasy, housed in the Patéras family pile.

The north industrial edge of the city, with its four landmark Genoese windmills extending out to sea, is known as Tampakíka; the island’s once important leather industry was concentrated in the huge empty buildings along the sea.

Kámpos: Genoese Gentility

The Genoese especially favoured the fertile, well-watered 600-hectare plain south of town they called the Campo, or Kámpos. Beginning in the 14th-century, they and the local Chian aristocracy built villas and plantations of citrus groves (oranges, lemons, bergamots and sour oranges), mastic trees and mulberries for silk, which was an important source of income until the 19th century.

The greatest fortunes, however, were made in shipping—grain, timber, cotton, hides and flax—from the Levant and Black Sea to western Europe, and transported luxury items back to the east. Their companies were run by extended families, including some who rose to national fame in Greece, including the Andreas Syngrou Benakis family, founders of the great history museum in Athens. Many only lived on Chíos part time, but the estate keeper (anestatis) at their mansion grew profitable citrus crops behind lofty walls.

Chians are famous for their reserve, but the inhabitants of Kámpos were (and still are a bit) downright secretive. You can read much more about this fascinating area now though, thanks to the Society of Kampos.

The tangerines and oranges were so precious they were wrapped individually in paper, sometimes decorated in gold; pickers had to have their fingernails inspected daily to make sure they didn’t accidently harm the fruit. They say in Russia a single orange cost a full day’s wage, making them a very precious Christmas gift.

Kámbos’s heyday ended in the mid 19th century. A devastating frost wiped out the citrues crops, which led to the planting of more cold-resistant tangerines, introduced from China. The invention of the telegraph made the Chíos network of up-to-date market information obsolete, followed by the aftermath of the American Civil War, which saw a huge uptick of grain exported to Europe, replacing the old sources around the Black Sea.

The local citrus crop declined even further when Greece joined the Common Agricultural Policy in the 1980s. Today only some 200 estates remain, produce juices and preserves—the Citrus Aroma company in the Karalis Mansion at Argenti 9-11 runs a Citrus Museum that explains the local culture and history. In recent years, tulips have also become an important crop.

Kámpos is an enchanting and evocative mesh of narrow lanes (best seen by foot or bicycle), full of secret gardens enclosed by tall stone walls, with gates bearing long forgotten coats-of-arms or the tell-tale stripes of the Genoese nobility.

Courtyards are paved with beautiful black and white pebble mosaics, and many still have (and use) their old water wheels (manganopigado) to raise the irrigation water atop their cisterns, today powered by electricity rather than donkeys. Without these there would have been no Kámbos.

Outside the walls the flowering meadows, wooden bridges and ancient trees create a scene of elegaic serenity unique on the Greek islands, especially in the golden light at the end of day. Several of the mansions have been converted into boutique hotels. You can go on tours with the Progressive Association of Kampos (FOK).

Mastodon bones were found at Thymianá, which was the source of Kámbos’ golden building stone. Sklaviá, named after the Greek slaves of the Genoese, is especially lush.

Outside the village of Vavíli is a hidden gem: the octagonal domed Byzantine church of Panagía Krína (1287), built by to two of the members of the imperial court of Constantinople - Efstatios Kodratos and Eirini Dukaina Pagomeni. The church is beautiful outside with its elaborate arches, arched windows, ceramic decoration and marble reliefs built into its corners, and beautiful inside, covered with frescoes from the 14th, 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. The guardian +30 22710 44328 is there from 8.30am-3.30pm daily except Tuesday.

The nearest beach to Chíos Town and Kámbos is at Karfás, the most resorty beach on the island, and reached by frequent blue buses. The sand may be ‘as soft as flour’ but there’s less of it to go around all the time as more and more new hotels and flats sprout up like kudzu.

South on the coast, Moni Ag. Minás (closed afternoons until 6pm). During the massacre in 1822, women and children from the surrounding villages took refuge there; a small, hopeless battle took place before Ag. Minás was overrun and all 3,000 were slain, their bodies thrown down the well. Their bones are now in an ossuary; blood still stains the church floor.

The Mastikochória: Mastic Villages of the South

Southwest of green Kámbos stretch the drier hills and vales of mastic land, where it often seems that time stands still. It must have special magic or secret virtue, for mastic bushes the refuse to be transplanted anywhere – even northern Chíos won’t do; the bushes might grow, but not a drop of mastic will they yield. In 2012, half of the mastic orchards were destroyed in a terrible wild fire, but the trees have since been replanted. Today it employs some 2000 people.

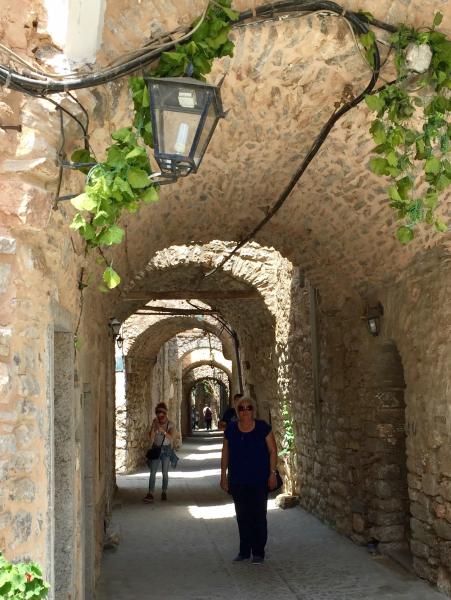

Nearly all the 24 villages where mastic is grown, the Mastikochória, date from the Middle Ages, and were carefully spared by the Turks in 1822. The Genoese designed them as tight-knit little labyrinths for defence, the houses sharing a common outer wall with few entrances; if that were breached, the villagers could take refuge in a central keep.

Heading south from Chíos Town, the first of the Mastikochória is Armoliá, which you’ll soon notice also makes ceramics. It is defended by the Byzantine Kástro tis Oréas (1440), a castle named after the beautiful châtelaine who seduced men only to have them executed.

Kalamotí, once one of the most thriving villages, has tall stone houses on its narrow cobbled streets and a pretty Byzantine church, Ag. Paraskeví, and isn’t far from the 12th-century church Panagía Sikeliá. The closest beach to both towns is sandy Kómi, a low key stretch of sand, reachable by bus; if it’s too busy, try Lilikas, 2km east.

Ancient Emborió

West of Kómi, before the old mastic-exporting port of Emborió, a new road zigzags up a hill to the site of ancient Emborio, where British archaeologists uncovered the island’s first Ionian settlement from the 8th-century BC.

There’s an explanatory film at the entrance; paths (hot in the heat of the day!) wind up the boulder-strewn hill, past houses and a megaron, to the enceinte of an ancient acropolis, with the ashlar base of the simple, rectangular Temple of Athena with its cella and outside altar, last rebuilt 4th century BC.

The wealth of amphorae found underwater at Emborió hint at the extent of Chíos’ wine trade (Aristophanes wrote that the ancient Chiots tippled with the best of them; these days their grapes go into ouzo or a raisin wine not unlike Tuscan vinsanto).

Beautiful Mávra Vótsala Beach, five minutes from Emborió, is made up of black volcanic pebbles—the source of Kambos’ beautiful mosaic pavements. Signposted along the beach road are the ruins of a 6th-century Christian basilica with a marble cross font and a few mosaics.

Pyrgí, Olympi, Mestá and the Mastic Museum

The largest mastic village, Pyrgí, founded in the 13th century is outrageously picturesque. Uniquely, nearly every house is beautifully decorated with xistá, the local word for the sgrafitto decoration taught to the locals by the Genoese: black sand from neary Mávra Vótsala beach is scraped over fresh white plaster, creating geometric, floral or animal-based designs. Pyrgí’s main square is particularly lavish.

Of the equally pretty churches, the 12th-century Ag. Apóstoli has frescoes from 1655 (open most mornings). Some say Pyrgí was even the birthplace of the best known Genoese of all, Christopher Colombus.

Outside the village is the Chios Mastic Museum, one of several across Greece dedicated to the country’s cultural and industrial heritage funded by the Piraeus Bank.

Walled atmospheric Olympi is built around a 68ft tower (that now contains a restaurant). Originally had only one gate; outside the walls by the little allotment gardens, a sign show a map of the Mastic Trail that links Olympi to Mestá.

Ten km outside town, off the road to Ag. Dynami beach, you can visit the stalactite Cave of Olympi and Mestá, the ultimate fortress or kástro village, with no ground floor windows facing out and only one entrance into its vaulted maze of lanes and flower-filled yards, now much beloved of film crews; at other times you can almost hear the silence. Two churches are worth a look: the medieval Ag. Paraskeví and the 18th-century Mikrós Taxiárchis, with a beautifully carved iconostasis.

Southwest Coast

The southwest coast is dotted with exquisite wild beaches; Fana, to the south, owes its name to the ruins of a fountain recalling the Great Temple of Phaneo Apollo (6th century BC) that stood nearby. Alexander the Great stopped to consult its oracle; several of its Ionic columns are in the Chíos Archaeology Museum.

The road north from Mestá to Chíos Town passes Mestá’s port of Liménas, Elata with its flat roofs (rather like ancient Emborio) and picturesque medieval Véssa, deep on the valley floor and worth exploring on foot. From here, another road leads north to Lithí, a pretty village with a so-so sandy beach below, tavernas and a few places to stay. Further up the wild west coast you can swim at the pebble coves near Elínda and circle back to Chíos Town by way of Avgónima and Néa Moní.

Inland from Chíos Town: Néa Moní

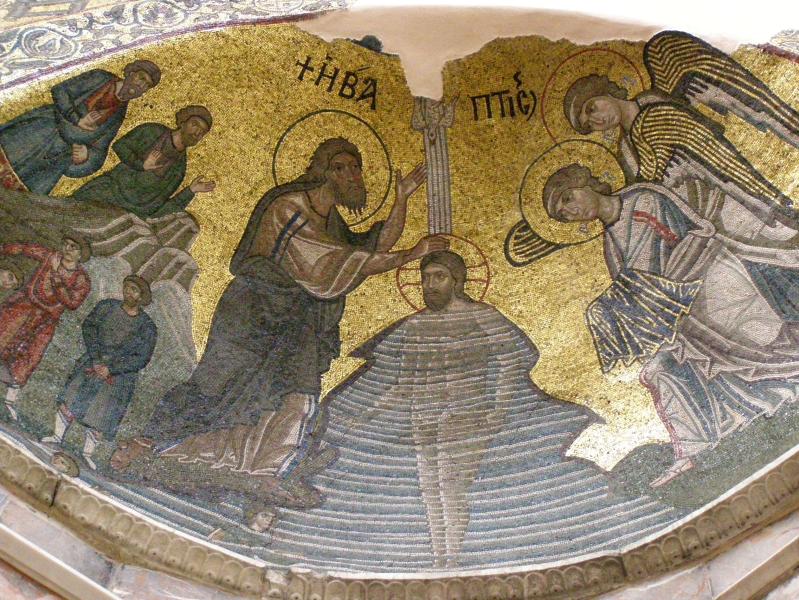

Perched high in the pines, Néa Moní is a UNESCO World Heritage for its rare and mosaics. You might want to take a taxi there if you don’t have a car; blue buses only go as far as Karyés, a mountain village flowing with fresh springs, but a long 7km walk from the monastery.

Néa Moní was ‘new’ in 1042, when Emperor Constantine VIII Monomachos (‘the single-handed fighter’) and his wife Zoë had it built to replace an older monastery, where the monks had found a miraculous icon of the Virgin in a bush; not the least of its miracles was its prophecy that Constantine would return from exile and gain the throne. In gratitude, the emperor sent money, architects and artists from Constantinople.

The church has a sumptuous double narthex and a subtle, complex design of pilasters, niches and pendentives that support its great dome atop an octagonal drum. Its richly coloured 11th-century mosaics shimmer in the penumbra: the Washing of the Feet, The Saints of Chíos and Judas’ Kiss in the narthex and The Life of Christ in the dome, stylistically similar to those at Dáfni in Athens and among the most beautiful examples of Byzantine art anywhere – even though they had to be pieced back together after the earthquake of 1881 brought down the great dome.

A chapel has the bones of some of the 5,000 victims (among them, 600 monks, women and children) of Kara Ali’s massacre who had sought sanctuary in the monastery.

From here, a rough road leads to the Monastery of Ag. Patéras, honouring the three monks who founded Néa Moní and rebuilt after the earthquake in 1890. Further up, medieval Avgónyma was built by convicts, who, having gained their liberty by building Néa Moní as their penance, decided to stay in the mountains. Fifty years ago it was nearly abandoned; now Greeks have restored much of it as holiday homes; it has become famous for its nature walks and over 100 kinds of wild orchids, thanks to writer and naturalist Giorgos Missetzis who runs tours from the Spitakia Cottages.

From here, a road zigzags up the granite mountain to the ‘Mystrás of Chíos’, the medieval village and castle of Anávatos. It witnessed horrific scenes in 1822; most of the villagers threw themselves off the 1,000ft cliff rather than wait to be slaughtered, and ever since then the place has been haunted.

Northern Chíos: Vrontádos and its Easter rockets

Northern Chíos is the island’s wild side, mountainous, stark and barren, its forests decimated by shipbuilders, and in the 1980s by fires, but it’s also where you’ll find the island’s two wineries. Many of its villages are nearly deserted outside of the summer.

Vrontádos, just a few miles north of Chíos Town, is an exception, a bedroom-suburb village overlooking a pebbly beach and row of seafront windmills, famous for its unique Orthodox Easter celebration.

Members of two hilltop churches. Ag. Markos and Panagia Erithiani some 400m apart and separated by a valley, fire hundreds of homemade rockets at each other on Sunday, as part of Rouketopolemos—an Easter tradition that has been celebrated since anyone can remember; some say 120 years, or maybe 200.

While the priests in both churches intone the midnight Easter service, parishoners aim to hit the bell of the opposing church, with homemade rockets, made wooden sticks and loaded with an explosive mixture containing gunpowder.

The locals are proudest of the Daskalópetra (the Teacher’s Stone), a rock throne over the sea where Homer is said to have sung, and where his disciples would gather to learn his poetry, although killjoy archaeologists say it was really part of an ancient altar dedicated to Cybele. The 19th-century Monastery of Panagía Myrtidiótissa nearby houses the robes of the martyred Gregory V, Patriarch of Constantinople.

Near Vrontádos stood Chíos’ first church, Ag. Isídoros, founded in the 3rd century on the spot where the saint was martyred. A later church to house the relics of St Isídoros (whose feast day only happens every four years, on 29 February) was built by Emperor Constantine, but it fell in an earthquake and was replaced by three successive structures; mosaics from the 7th-century version are in the Byzantine Museum in Chiós Town.

After the Turks damaged the last version of the church in 1822, it was never rebuilt, perhaps because the Venetians snatched Isídoros’s relics in the 12th century and installed them in St Mark’s. In 1967 Pope Paul VI ordered them to return one of Isídoros’ bones, which is now kept in Chíos Cathedral. Vrontádos now gets by with a picturesque modern chapel to the saint, out on the sea rocks.

North of Vrontádos

Further north is Langáda, a very charming fishing village, sporting an array of bars, cafés and fish tavernas.

Jagged rocks surround Kardámyla, the largest village of northern Chíos and cradle of some of the island’s shipowners. Kardámyla is actually two villages, 2km from one another: the picturesque upper town and the seaside Mármaros, graced by a statue of the Kardámyla sailor paid for by the shipowners.

To the north, pretty Nagós Beach is set in a green amphitheatre and can get very busy in summer; its name is a corruption of naos, or temple, for there used to be one here to Poseidon. At nearby Gióssona, named after Jason of the Argonauts, there’s a pebble beach, more exposed than Nagos, but with fabulous turquoise water.

The road between Kardámyla and Pitiós rises through startling wild landscapes, with views of Inoússes far, far below. A striking village with its 12th-century tower, Pityós claims to be the birthplace of Homer; the locals (there are only 40 full time residents) can point out his ‘house’; today, you can point your phone at the QR codes scattered a round the village and learn its history and hear its songs. For more, see Pityos Destination.

West, over Chíos’ highest mountain, 1186m Pelinaío (at the pass there is a wonderful viewpoint, taking in most of the island) the 13th-century Moní Moundón with its rare (in Orthodoxy) depictions of the devil, is strikingly set between Dievcha and Kipouríes. Like Néa Moní this was a wealthy monastery, full of aristocratic monks; rebuilt after its destruction by the Turks in 1822, it preserves a series of good paintings going back to 1620.

Volissós

Byzantine nobles out of favour were exiled in the medieval castle at Volissós, a striking hill town that like Avgónyma in the south has enjoyed a new life thanks to holiday makers—many of them Greek—in search of authenticity with creature comforts. The castle was founded by Belisarius, Justinian’s general, although what you see was rebuilt by the Genoese.

This village also lays claim to Homer; in ancient times it was the chief town of his ‘descendants’, the Homeridai, who claimed that a local shepherd named Glaukos introduced Homer to his master, who then hired the poet as a teacher. Soon after Homer married a Volissós girl, had two daughters, wrote the Odyssey and set sail for Athens but died en route on Íos. A path from Volissós takes in the watermills along the Malagiotis Valley.

The sandy beach below the town, Skála Volissoú or Limniá, has traditional tavernas, a few rooms to let and a bust of Admiral Kanáris. Caiques go several times a week to Psará (the shortest way of getting there).

There are other excellent beaches near here, just as minimally developed: pebbly Chóri just south, the unofficial nudist beach, long, mostly wild sand and pebble Mánagros and Límnos, on the road to the Monastery of Ag. Markélla. This is dedicated to the island’s beloved 16th-century saint and favourite pilgrimage destination; one of Chíos’ finest black beaches lies just below.

North of Volissós two roads brave the wild, barren country. The westerly one climbs to little Piramá, with a medieval tower, and the church of Ag. Ioánnis with old icons. Parpariá to the north is a medieval hamlet of shepherds, and at Melaniós many Chiots were slain before they could flee to Psará in 1822.

On the northwest shore, the remote village of Ag. Gála is named after a frescoed 15th-century Byzantine church of Panagía Agiogalousaina (‘Our Lady of the Holy Milk’) in a cave in a green ravine (you’ll have to ask around for the key), which drips whitish deposits, or milk (gála), said to be the milk of the Virgin. There’s a legend (as usual!) that Byzantine emperor sent his leprous daughter to Chíos, and she hid in this cave, surviving on the liquid which miraculously healed her. The chapel has a superb iconostasis, with a icon of the Virgin, who has a rare little smile.

For less holy terrestrial secretions, make your way along the rough coastal road east to Agiásmata where Chiots come in the summer months to soak in the magic thermal baths or in the rocky pool near the coast. Above is the small medieval mountain village of Leptópoda, which looks like a fort from the distance because the houses are so close to each other.

Tourist Information: Chios Travel Guide

Chíos has a small domestic airport; ferries from Pireaus take 7 to 13 hours. There are also ferries once a week from Thessaloníki.

Images by 17qq, Arthur Pennant, Chios.gr, disou13, followJoseph, Güldem Üstün, Mariolovre, Meltedrainbow, Pascal Mages, PD Art, Pitropakis, P'Tille, RomkeHoekstra, Stylkontoz64, Vangelisg4