- Read offline

- Access all content

- Use the in-app Map to find sites, and add custom locations (your hotel...)

- Build a list of your own favourites

- Search the contents with full-text search functionality

- ... and more!

Zákynthos (Zante)

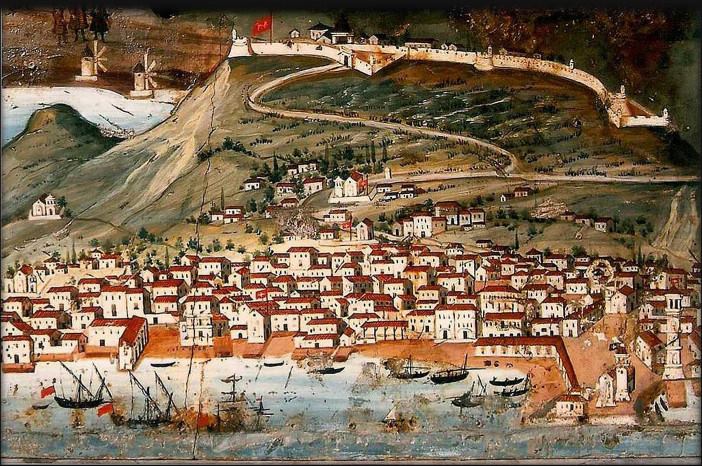

Of all their Ionian possessions the Venetians loved arrow-head shaped Zákynthos the most. Zante, fiore di Levante – ‘the flower of the East’ – they called it, and built a beautiful city on its great half-moon bay, which the earthquake in 1953 turned to rubble. Most of the villages were severely damaged as well: often a bell tower was the only thing left standing.

Nevertheless, the disaster did nothing to diminish the soft, luxuriant charm of the landscape. The hills planted with grape and currant vines (most of the ones in your scone are grown from the island’s native small seedless grapes), the olive, citrus and almond that fill the lush fertile plain in the centre and beautiful beaches that line the south and northeast coasts, hosting most of the resorts/

The Kéri peninsula and west coast (site of the famous but now off-limits ‘Shipwreck Beach’) is lined with spectacular white cliffs and caves and coves.

And if the buildings are sadly gone, the Venetians left a lasting impression – many islanders have Venetian blood, which shows up not only in their names, but in their love of singing.

Too much of a good thing?

A different Zákynthos used to make the headlines, thanks to the young tourists who flock to Laganás a party venue. The fact that they chose one of the most fragile environments in the Mediterranean for their all-night parties – the nocturnal nesting grounds of the loggerhead turtle – was unfortunate, although things have improved since the 1980s and 90s.

Even so, according to Which? magazine in May 2025 the island currently tops the charts in Europe when it comes to tourists per inhabitant—a whopping 150 overnighters to each local. The islanders have yet to hit the streets in protest (unlike the residents of the Canary Islands, or Barcelona)

History

Zákynthos has one of the most complicated histories of any Greek island. You can read about it in the most excruciating detail here, but below are the main points.

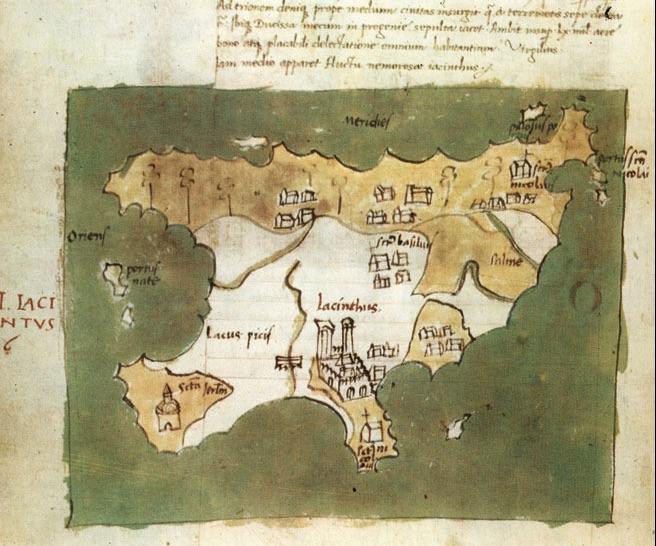

Tradition has it that Zákynthos (with its -ynthos ending, a pre-Greek Pelasgian word, like labyrinth) was named after its first colonist, a son of Dardanus from Arcadia in the nearby Peloponnese, who introduced the Arcadian love of music that would always characterize the island.

Zákynthos fought under Odysseus at Troy, although when he returned home and shot 20 of the island’s nobles – Penelope’s suitors – Zákynthos rebelled and became an independent state. It set up colonies, most importantly and (distantly) Saguntum in Spain, a city near Valencia that would later be demolished by Hannibal.

Levinus took Zákynthos for Rome in 214 BC and, when the inhabitants rebelled, he burnt every building on the island. Uniting with the Aeolians, the islanders forced the Romans out, although in 150 BC Flavius finally brought them under control.

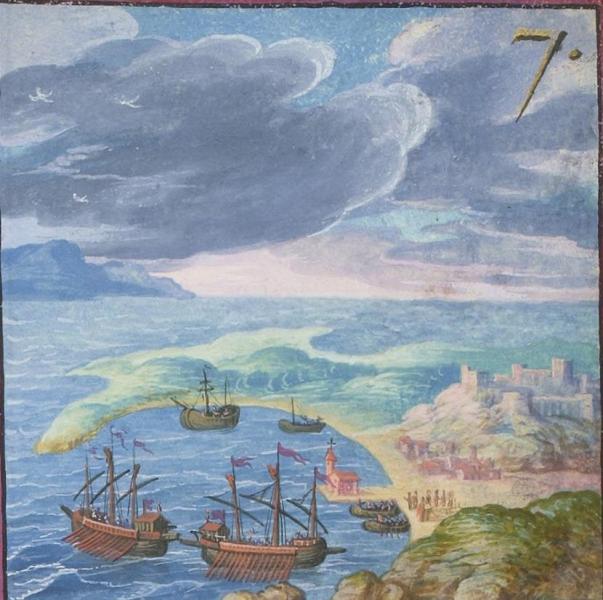

In 844 the Saracens based in Crete captured Zákynthos; the Byzantines expelled them, until 1182, when King William II of Sicily granted his Greek admiral Margaritos of Brindisi the island as part of the County Palatine of Kefaloniá.

After several other successors, Zákynthos passed to the Venetian Tocco family, who held on to it for almost 350 years, taking in refugees from the Peloponnese after the Ottoman conquest (while paying a tribute to the Sultan); Zákynthos itself had an interval of Turkish rule between 1479 and 1482, when it was reconquered by Venice.

It was an eventful period: the overweening privileges of the Venetians and wealthy Zantiots provoked ‘the Rebellion of the Popolari’, when the commoners seized control of the island for four years.

The influx of artists after the fall of Heráklion (1669), made Zákynthos the centre of a productive Cretan-Venetian Ionian school of painting. The Cretan-Venetian influence in local music gave birth to the island’s serenades, the kantádes.

Major poets were born on Zákynthos: the Greek-Italian Ugo Foscolo (d. 1827), Andréas Kálvos and Diónysios Solomós. Fired up by the French Revolution (along with the rest of the Ionians, Zákynthos would briefly become part of the Départements français de Grèce). Remembering the spirit of the Popolari, Zantiot republicans formed a Jacobin Club and destroyed the rank of nobility, burning the Libro d’Oro that accredited the island aristocracy.

In 1798, the Russians forced the French garrison and the inhabitants to surrender, and, when the British Septinsular Republic established an aristocracy of its own in 1801, populist, high-spirited Zákynthos rebelled again.

Many joined the Filiki Eteria (Friendly Society), supporting the Greek War of Independence. Many rebels in the Peloponnese, notably Kolokotrónis, found asylum here before returning to fight some more.

The Second World War

The island’s feisty spirit revealed itself during World War II, when Mayor Loukás Carrér and the Bishop of Zákynthos, Chrysóstomos, stood up to the Nazis, who demanded that they hand over a list of all the Jews on the island – there were 275, all hidden by the islanders in remote villages.

The list, when Chrysostomos handed it over, had two names on it: his own and the mayor’s. ‘Here are your Jews,’ Chrysostomos told them. ‘If you choose to deport the Jews of Zákynthos, you must also take me and I will share their fate.’ In 1978, both the bishop and mayor Loukás Carrér were awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations.

In spite of the Nazis’ best efforts, no islander ever betrayed a single Jew. It’s a remarkable story and recently the subject of an American documentary, Life will Smile (2017)

Then came two earthquakes in 1953, which destroyed nearly every building on Zákynthos. And the first to send aid was Israel; today, after the earthquake, the only sign that they were ever here is the Jewish cemetery in an olive grove just above Zákynthos Town on Bochali hill.

Since then the island has been shaken up twice by earthquakes, including one on October 2018 measuring 6.8 on the Richter scale, causing landslides in the south.

Images by Dionysios Tsokos • Public domain, dronepicr, Nikolaos Kalergis, PD art, Public Domain